S T A V E

XXVIII

8th March, 1778

A fine spring day and the generals in an open carriage. Tulips in gardens of the well-to-do, Johnny-Jump-Ups in window boxes violet, yellow and blue; crabapples, cherries and peach in full bloom, a pastel sky, cotton clouds – a perfect day of the Late and the New. One of beginnings. So thought Billy, Mrs. Loring at his side, sitting opposite Henry Clinton who’d just arrived.

Howe chatty, as if the history with Clinton had been undone; they were out for the morning air, Billy as tour guide as they drove down Water Street, pointing out Philly’s eccentricities and charms as if a Native and the Descendent of Pitt himself: there – Cornwallis marched the grenadiers and how the city turned out to cheer, there – Washington slept before hightailing it to Valley Forge, the theatre district – you should see the marvelous plays, Andre, Cathcart, Rawdon and Watson – talented fellows; the Grand Masonic Lodge and Billy its Right Worshipful Grand Master for the year; the docks, oh, my claret’s been brought ashore; there – my favourite coffee bar; how ghastly the city before the river’d been opened, but it’s a wonderful place – perfectly modern, American in every way.

Along the riverfront, Billy spied the frigate to take him away. He was ready; the relationship with Lord Germaine had, over the winter, deteriorated – the American Secretary demanded he act. And he did . . . with little effect: forever trying to lure the Enemy into a trap, an Enemy hard to bait. And the few times they did, the Regulars knew no bounds; just days ago, they cut off the limbs of Rebel captives and set them alight when they could not move. The Rebels did no less to British prisoners. The Face of War and only a Fool thought different. But Billy had other concerns – his resignation and the official word. His Majesty had but two choices: act on it or fire Lord Germaine.

It came in the person of Henry Clinton, the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief. Billy would retain the command until his departure, as it should be, at least to his way of thinking. Why confuse things? Besides, he hoped for one more chance at Washington – a final blow. Otherwise, nothing more, the best had been accomplished in spite of dictates from the Home Office. How little the Government understood, especially Germaine – no concept of terrain, the land’s expansiveness, the American temperament. Would Germaine think fifty thousand could subdue all of Europe? One hundred fifty thousand would not do. And supplying an army on the Continent was difficult enough much less one over a fickle ocean – London to Warsaw the same as Savannah to Boston. And Billy’s done his part: New York, Philadelphia and Newport back in British hands. And this business of Burgoyne, he would not take that on. There’s a rumour Philadelphia is to be abandoned. A crime if true; this army did so much to take it, and the loyal Americans . . .

He smiled at Betsy, her diminutive form against the Spring day – a picture Mr. Gainsborough might paint, all diaphanous and dreamy, a whiff of an image as the carriage moved by, and himself a Gainsborough character – easy going and overdue. He’s going home the Great Man to face the knobbos, those clever, specious men who don’t know what they don’t know, with ill-informed opinions, or worse, informed just enough. He’ll battle them down through the Ages, defending his command and always one question: What was Billy thinking? No matter, Captain Hale penned it best writing to his parents:

“Whether you can send a better Gen. than Sir William Howe, I know not, one more beloved will be found with difficulty.”

Billy’s men – no army better served, but their story too will be lost – the Grand Army of ’76-77, the Army on American Service, quick at the heel, hard on the bit, punch and thrust at its zenith. Will Britannia see their like again? They earned Celebration. And would receive none returning home.

In the distance, a sharp crack, inconsequential noise that did not matter, but in Billy’s mind the face of John Sherwin on Breed’s Hill and then the same sharp crack of a ball taking off the top of his head. Billy saw it as he saw the pastel backdrop, as he saw the wharf and the Delaware beyond, as he saw the somewhat aged yet still cherubic face of Henry Clinton. He took Betsy’s hand as John Sherwin fell.

Clinton marked him. “Regrets?”

“Not in the least. I’m the good old soldier and fought the old good fight. It’s time.”

Clinton nodded and Betsy with a doleful smile, prompting Billy to rattle on.

He bequeathed all to Clinton with comic art: the Army, the City, the Swamps and the Burghs, the people’s Good Will, even Betsy if he would have her . . . But what would Clinton do with Betsy, the old girl? Clinton had Mrs. Mary Baddeley, a sergeant’s wife, more a spouse than mistress since his own wife had died, and the sergeant more brother-in-law than Cuckold. No, for Betsy, she had but one other bed and that with her husband, a gambler who had already left her once to seek his fortune. Billy would miss her energy. He would return to Lady Howe, a coquette herself with many dalliances.

“You know of the grand fete?” Billy asked about the celebration in his honour.

“I’ve heard little else,” Clinton said.

“What have you heard?” Billy boyish.

“A flotilla, a parade, some type of tournament and then a grand ball.”

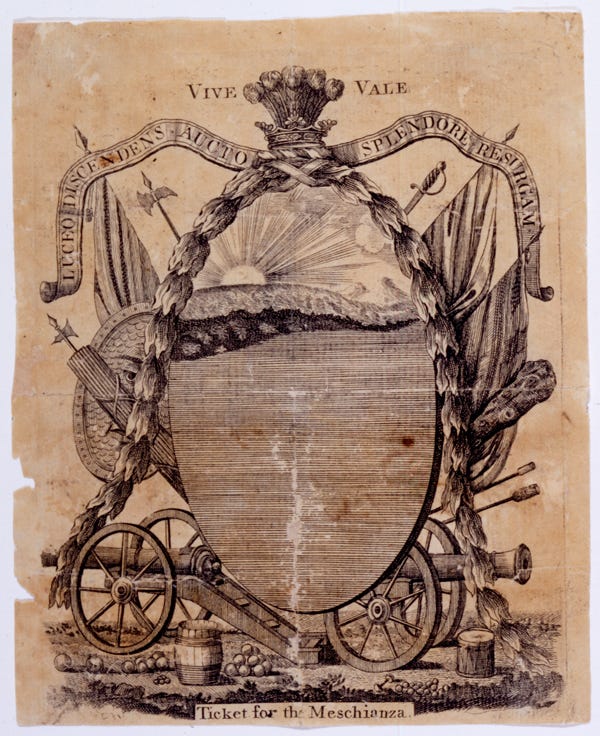

“‘Meschianza’,” Howe rolled it on his tongue with delight. “Have you seen the tickets?” He reached into his inside pocket. “This one’s yours.”

“Impressive chit,” Clinton said.

“John Andre, one of my aides-de-camp – drew it himself. Clever fellow. He and Delancey painted the scenery for the festival. What a fine lot. Put them to good use. I shall miss them.”

“No doubt you shall.”

“They’re good, Harry,” Howe said of the army. “Treat them well.”

“I shall not do otherwise.”

“Of course, there are the Court Martials. Extraordinary entertainment, not that you not know. Some quite sad and bizarre. A young corporal was set to baby-sitting a nine-year old girl, the daughter of a private and his wife. They said they caught him in the act with her. The fellow in hysterics denied the charge. He was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.”

“Did he do it?”

“Upon examination, the little girl had been violated.”

“Then well should he be,” Clinton said. “And beaten as he chokes.”

“One would think.”

“What happened?”

“This is the most bizarre part: Miss Rebecca Franks, the Rebecca Franks, toast of the town and object of every officer’s desire, she comes to me, in tears. Pardon the boy she says. I ask her, ‘What is this boy to you?’ She says he has done her and her family many services, that he is the sweetest and kindest boy she has ever known with no temperament to be a soldier. She’s amazed he has survived in the army thus far, yet alone be made corporal.”

“You refused?”

“How could I refuse? She’s the daughter of a prominent loyalist. I deferred it to the King. I wrote to Germaine confirming the sentence and that Miss Franks desired a royal pardon.”

“What happened?”

“His Majesty give clemency? He most certainly did not. I hanged the boy. Would’ve done it regardless, though Miss Franks is a lovely creature.”

“And to the point?”

“This is a city tied to this army. Their wellbeing is contingent on its staying.”

“I understand,” Clinton said, “but that decision is out of my control.”

“I would think the Commander has some control.”

“The American Secretary has moved all stratagems under his purview.”

“Well,” Howe quipped, “I have not lost an army.”

“Neither have I,” Clinton said. “I did my part. I opened the Highlands.”

“Of course you did.”

“He should’ve known whether or not to push, and could’ve turned back for Canada or

Fort Ti for that matter and tried again next year.”

“Burgoyne has a cavalryman’s judgment.”

“No judgment at all. He does not know America like you and me.”

“And we have not lost an army,” Howe repeated.

“Or the war.”

“But there aren’t enough Regulars in the world to win it,” Howe said. “They didn’t send half the men needed. The army is but a stick to get them to the table. Diplomacy has always been the Key. We can beat them from morning till night and ourselves undone if we receive a single check. Any check must be avoided. There – that’s the total of my wisdom. But you should have no problems; Washington is still frozen at Valley Forge. It’s a wonder he has any army left.”

Moving onto Cedar Street, they drove to Second turning south. Once in the countryside, they stopped before a large stone mansion. Within two hundred yards, carpenters erected a long canvas roof structure for the chametre de fete. “If you look over to the riverbank, you can see the ceremonial arches: one for the Army and the other for the Navy. The amphitheatre and pavilions are being built over there.”

“I see,” Clinton said, masking his discomfort.

“They’ve chosen a Turkish theme. Knights shall joust for the honour of local ladies in costumed regalia. Damn if they might darken their faces like Moors. Who knows all they’ve planned? We might be sitting ‘round hookahs drinking coffee through the night.” He considered the mansion, Walnut Grove. “Fine house. The Philadelphians build them as strong as castles.” He nodded with satisfaction. “Well now, we ought to head back.”

Upon approaching Howe’s headquarters, agitated townsfolk crowded around the door.

Howe thought they protested his going. When the carriage stopped, he stood. “Be assured good friends, the situation is well in hand. Sir Henry is here and there will be a smooth transition. Lord Howe still remains and the two of them will see to all your concerns in an efficient manner.”

“Sir William,” spouted the prominent Mr. Galloway, “Philadelphia is our home. We cannot leave again. Who will protect us?”

“Sir,” Howe cautioned while helping Betsy from the carriage, “I said Sir Henry is here.”

“But Sir William . . .”

“Mr. Galloway, when has this army ever not served you?”

“Then you will evacuate us when it goes?”

“That is a rumour.”

“Then the army will not go?”

“I’ve been given no such order,” Howe said. “Good friends, Sir Henry has only just arrived and I am still with you. We will entertain you shortly and give you the time you deserve. You shall receive invitations. The army is here and you are here. Thank you, good friends.” He entered the house before another word.

Tea in the baroque parlour on Chippendale and Affleck, the finest suite in the colonies either general had seen – Howe on an easy chair with ‘hairy-paw’ feet, rare for this side of the world with the vivacious Betsy serving tea. Who wouldn’t stay in the cold winter and fuck all the day, thought Clinton.

They chatted about the city, about who was who, and who was doing what to whom. And when finished, Betsy curtsied in a most charming manner and off with a peck on Billy’s cheek. Clinton then presented two sealed dispatches. Howe read the first without reaction: his official recall and France has signed an alliance with the Rebels – nothing new in that. But at the second, his expression knotted: France has declared war with a squadron heading for American waters.

He handed the dispatch to Clinton. “You know of this?”

“In a manner of speaking.”

“How it grows,” Howe said. “Who else will get into it? To think – another global war.”

They stared at each other and the rivalry abated.

“I’m ordered to withdraw from Philadelphia,” Clinton said. “The American Secretary no longer finds it of strategic use.”

“Everyone’s fear.”

“Washington knows this?”

“He has his spies.”

“At first I was to break up the army,” Clinton said. “Send 5000 to St. Lucia and 3000 to Savannah and then withdraw to New York and see what the Peace Commissioners could do. If they failed, I was to evacuate New York for Newport, or abandon the colonies altogether for Halifax and await new orders. But now the French are coming, the army stays.”

“Maybe the Peace Commissioners can pull it off,” Howe said.

“We can give the rebels the world, but not what they want. They’ll never come to terms now France is in it. His Majesty has no intentions of letting America go.”

“Maybe he should.”

“Maybe. Let them settle their own affairs.”

“They’ll murder each other.”

“They’re murdering each other now,” Clinton said. “I disdain marching out of Philadelphia with our tail between our legs.”

“I will try to end it here so that will not happen. My hope is to draw Washington out to fight. Bag him in an open battle and then the Peace Commissioners can do their work.”

A knock on the door and Howe’s aide entered. “Sir William, the townspeople have pushed past the guards into the foyer. They’ll not be turned away and insist on seeing you.”

“Very well.” Howe turned to Clinton. “You should be in on this.”

In the foyer, the same prominent men minus Joseph Galloway. “General Howe! General Howe!” they cried. “We want the truth! What does the army intend to do? We demand to know!”

“Gentlemen, curb yourselves,” Howe commanded from the landing. “I’ll not be howled at. I’ll field your questions after you’ve come to order.”

“We’ve heard France has declared war and the army has been ordered to evacuate Philadelphia,” a well-tailored merchant shouted.

Howe leaned on the banister. “I must say you act as if this army has never looked to your safety, that it has never shown concern. I ask you remember his Majesty’s firm resolve to protect your rights and liberties. As for France, they have signed an alliance with Congress and declared war. What of it? When has Britain not handled France? Let it be done, I say and finish what had been started in ‘63. The French have no concern for the rebels; they would dash them as soon as fight on their side. And what can they do? Louie is a pauper king as his fat wife spends him into ruin. So far all they’ve sent is a boy to lead Washington’s scrawny troops. Sir Henry here will set them right.”

“But you are leaving,” another merchant said.

“Not too soon. I think I’ll stay a week or two, enough to see what Sir Henry and I can get going. I cannot offer more.”

“But is the army leaving?” they asked.

“Some questions do not serve your best interest,” Howe replied.

A moan.

“If the army should leave, will it take us with it?”

Howe turned to Clinton. “The army will do its part.”

“And if it does not?”

Howe bristled. “You shared Philadelphia with your rebellious countrymen before we came, surely you will come to terms with them. You’re not the type to be pushed about. Make peace with them. That has always been the chief goal. His Majesty desires to win them back.” He huffed. “Why do you make me answer you so, good friends. When have I ever failed you?”

“General Clinton,” a merchant asked, “when do you take command?”

Clinton stammered. “Why, I am in command.”

“Yes,” Howe interjected. “We’re both in command.”

“What can you tell us, Sir Henry?”

“America is dear to me. I grew up in America. You are my countrymen. I offer you my protection whatever the course. No man should feel unsafe in his own house. You have the army’s protection wherever it should go.”

“Good friends,” Howe rejoined, “do not despair. The new peace commission has yet to propose terms to Congress. Washington is battered and weak. Can he last another month? How long will it take France to act? A year? Two years? One thing I can assure you: the army remains as long as I am Commander-in-Chief.”

******************

“What shall we do?” Obedience lay with Geordie in the black of the summer kitchen. “I don’t want to leave. Philadelphia is like home. I don’t want to leave Mrs. Edmonds. I don’t want to sleep in a tent. I don’t want to go back to the brigade. I want to stay here.” Geordie, just back from the company’s tour in the northern redoubts, had no thought beyond this night. “Doesn’t it frighten you?”

“It does.”

“What frightens you?”

He sighed.

“Geordie, what frightens you?”

“Battle frightens me. Change frightens me. I want things to stay the same.”

“Nothing stays the same,” she pronounced bitterly.

“Hearts stay the same.”

She didn’t answer.

“Obedience, your heart is the same.”

She stared into the dark, imagining the angles of the summer kitchen and the familiar feeling of the mattress on the floor. “Yes, still the same.”

He held her as if she might run away.

“Don’t.” She pushed against his arms. “You may not possess me. I’ll not be possessed. I married you to save me, not for love. Oh, I intended to love, but the way women convince themselves to do. A husband becomes one more thing. But I fell in love with you.”

“And that was not your plan.”

“I had no plan. I never think ahead. Hearts do not think. They do. But whatever, you may not cling to me.”

He released her, but she put his arms back. “I didn’t say to let me go.”

“But you said . . .”

“Men are stupid . . . You demand my heart.” Her voice resentful.

“That’s wrong?”

“It’s the only thing that’s mine.”

“You demand my heart,” he said.

“It’s not the same.”

“Not the same?”

“Not the same. Men have had my body and for them, that matters. And I’ve given them everything else: my duty, my patience, my compromise. I’ve been what they’ve wanted me to be. And you – you’re not safe.”

“Whatever do you mean?”

“You must not know what’s in me before I do.”

She then pulled him tight and pressed so hard as to cocoon inside him.

“What I fear most . . .” he said.

She pressed his lips. “No more talking.”

******************

Libby and Rachel, in the crowd, watched the Hessians on the Center Commons. Sir William and Sir Henry stood in the viewing stand on the edge of the green while the remainder of the British command sat ahorse as the regiments, in slow step, paraded with the music, the guttural German commands in a prolonged rolling tongue, the snap of the arms to poise to advance, officers dipping their swords in present, Hunter Green and Prussian Blue crossing before the regimental Colours. How grand. How very, very grand Libby thought in spite of her upbringing. Exotic, the Hessians, with their waxed moustaches and long queues, nothing American in their dress and demeanour, only opulence and vanity, whimsical to Libby’s eyes. But in truth, nothing of whimsy about these men; they’d pull a girl down and pop her open like a sack of grain then leave her for the rats. So she heard. It was true. Every day it was true. Yet, there are good men, she thought, God-fearing men of charity and kindness. She tried to pick them out, but good men and criminals looked the same – the uniform transformed them with a fearful knowledge she could not grasp – their kindness truly kind, and their crimes brutal. Libby and Rachel held hands, that they would dare such danger.

General Von Knyphausen rode at the center on a skittish new mount. A tough old bird, Von Knyphausen, held the steed in check with a single taunt hand, but as he poised his sword while passing before the viewing stand, a blast of wind snapped the Colours before the stallion’s face. It reared, but the stolid general, intent on ceremony, presented his sword even as he slipped over the mount’s croup to land with a plunk. Libby squeezed Rachel’s hand. How the Rebels would laugh, but not Libby, and not Rachel in her mistress’s presence. But Von Knyphausen stood before his aides could assist him, remounted without scorn as the music marked time and then all carried on without acknowledgement.

“That was sad,” a voice sounded from behind the girls. Libby turned. Elliot.

“Mr. Elliot,” she said somewhat breathless, followed by an uncomfortable smile. “Thou gave me a start.”

“My apology.”

She held tight on Rachel’s hand, bent on the parade. “Not to worry.”

Elliot fell in next to her. “A sad sight,” he said again, embarrassed for the old gentleman.

“Yes.” Her voice pressured.

“Humiliation.”

She looked up at him. “Difficult for us all.”

“What can go wrong, will,” he said. “An odd providence.”

A Hessian march filled the air. An odd providence indeed, that he should find her here. Had he followed her? No sign of him when she and Rachel stepped from the alley, and Libby had been vigilant walking through the town, looking about as she and Rachel had headed down Second Street to view the construction at Walnut Grove. Had he been a labourer there? But no, he was in his regimental neat and clean.

“Foot Guards seem to wander about. I should think thee be on some duty.”

“I came off an hour ago.” He shook his head. “In truth, snuck away. Our officers are rarely present; they practice jousting for the fete, they recite lines for plays. Our sergeants and corporals assign us duties, but then go off themselves. And since we completed our rotation in the lines, we do what we will.”

“How enviable, Mr. Elliot – to do what thee will.”

He looked at Rachel staring him down. “No ma’am. I do not so much do what I will, not since the day we met. I told you the truth about my coming here.”

Her brow pinched.

“I see,” he said, doing the same. “It’s rumoured the army will leave. You can take your ease.”

“Mr. Elliot,” she said despite her better judgment, even with Rachel jerking on her hand. “Can we not be friends?”

“That is something I know little of.”

“Can thee not try?”

“I have.”

Fearing onlookers might hear, Libby gestured toward what must’ve been the last full tree in Philadelphia. “Try again,” she demanded. “Friendship.”

Elliot stared at her hand in Rachel’s. “Must she hear?”

“Rachel, stand over there,” Libby ordered softly.

“No Miss, your father – ” Rachel countered.

“Rachel, please,” Libby said, but regretted it.

“Miss Libby – ” Elliot paused, hearing himself. How odd he speak her name, and not the name he wished. “I require more than friendship, and if it is still what you seek, then I’ll do my best to give it. I would marry you and bring you back to the brigade.”

“Marry?” she said like a vulgarity. “Mr. Elliot, we are of different worlds. Whatever would bring thee to that inclination? No encouragement from me, I assure.”

“I – ”

“Do not say it.”

“Miss – ”

“Do not say it! Do not make me hurt thee.”

He stared through her and then at Rachel. “What can you do that’s not been done?”

“Mr. Elliot, that day, did thee truly receive Christ Jesus?” A Quaker sarcasm.

“I thought I did.”

“Did thee ask?”

“Yes.”

“Then He has not failed thee,” she said almost clipped. “Know it. Accept it.”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“It matters most of all.”

“All right then, will you fail me?”

“I’ll not fail you as a friend and a fellow Child of God.”

“Not enough,” he said.

She reached out for Rachel to save her, the martial music growing louder. Elliot with a dark rising. The facings on his regimental tugged on the hook & eye of his coat and the pewter buttons flashed sunlight from his expanding chest. Something reaching out from him. She could feel it.

Elliot turned and they left.