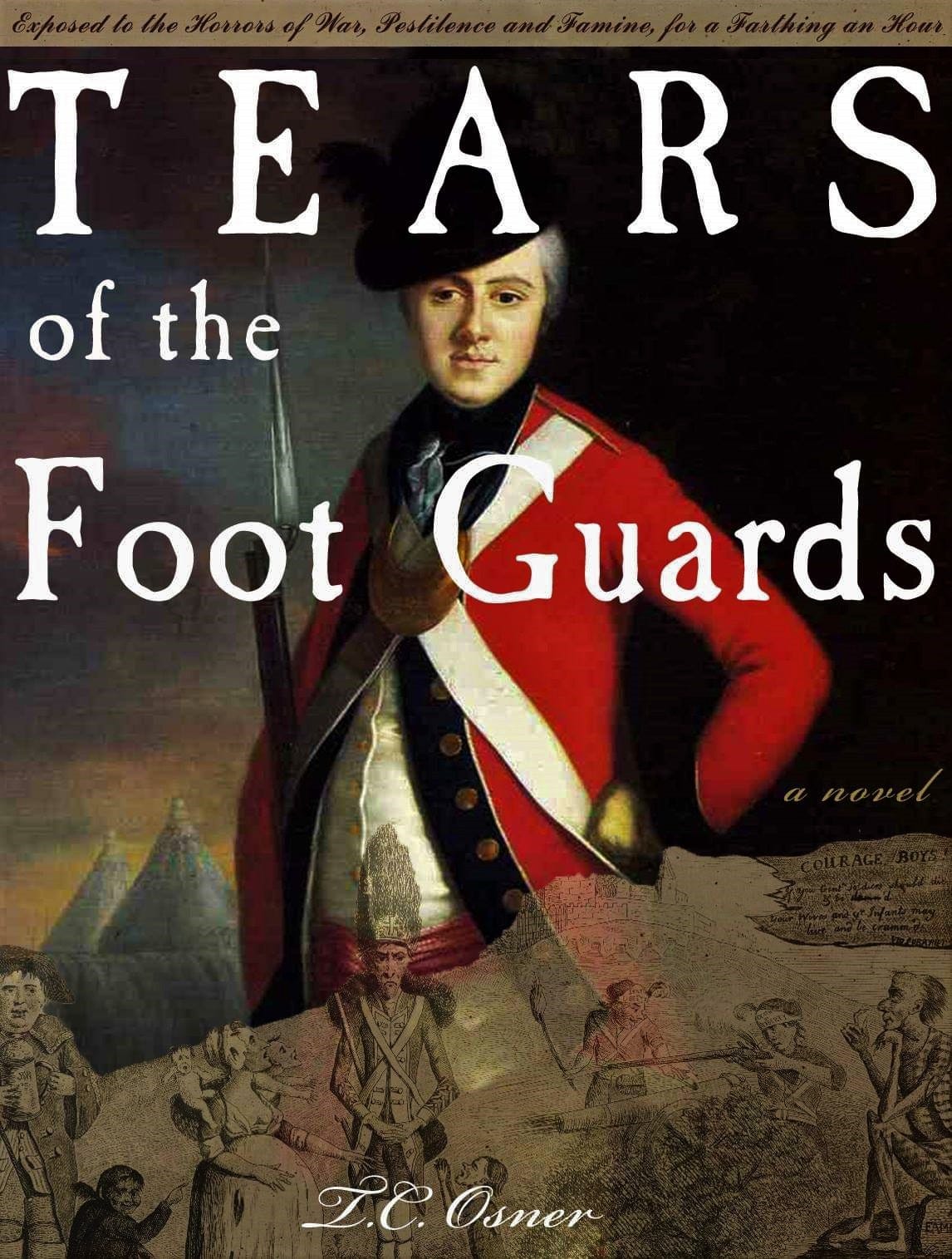

TEARS OF THE FOOT GUARDS

ALLEGRO - STAVE XVI

S T A V E

XVI

25th December, 1776

Obedience smiled – to cook in a kitchen: cranes and spits in an open hearth, fatback crackling, a roasting hen turning, pots bubbling with chowdered corn and in the beehive, Indian Pudding. The firebox, blackened since Cromwell’s day, was the crowning jewel of the old stone manse – the generations that tended it, having birthed and died and never knew England. And the kitchen larger than the flat on Old Pye; she could sit in a chair, she could stir without bending; no earthen oven to share, but a fine house with a fine barn and numerous outbuildings for her first American winter. Killer that it is: frostbite, the flux, la grip. Surer than a musket ball; most burst their hearts from the coughing. Though occasionally a wife might succumb from a drunken husband . . . but also him from her as well to be honest. Obedience feared all but the last; Geordie proved a kind soul, a lucky catch – lucky so far. And lucky again when they cantoned here, in Middlebrook, a fine New Jersey village.

They had married last week, going into winter quarters. The license procured from the local parish and the ceremony performed by the brigade chaplain, Reverend Mr. Cooke, in the barn. The Company witnessed, standing about the stalls and lofts, and Mr. Cooke, mono-chromatic in black with white tabs: “. . . the mystical Union that is betwixt Christ and His Church: which holy State Christ adourned and beautified with His Presence and first miracle that He wrought in Galilee . . . commended to be honourable among Men, and therefore is not to be enterprised, nor taken in hand unadvisedly, lightly or wantonly, to satisfy men’s carnal lusts and appetites like brute beasts that have no understanding; but reverently, discretely, advisedly, soberly, and in the Fear of God . . .” God, yes, yes, God . . . What’s He got to do with it? About them in the candlelight the soft cardinal red, everyone watching, all her life, people watching. How’d she come to this? “You needn’t fear, madam,” Captain Leigh had inclined toward her, “Private MacEachran is of good character.” Good character? Is anyone? Bolt. Run – back to Old Pye, back ‘round Birdcage Walk – and sing ‘til you’re noticed – a businessman, an officer, wring ‘em and toss ‘em when done as becomes a great lady . . . She stared at Geordie. Companionable . . . Under the sycamore – his big cock . . . while it lasted . . . but he loves. Loves what? No Smithfield bargain . . . The fool’s a romantic. But there – Grace on her husband’s arm. Jaruesha and Tom Tree a breath a part. About the barn faces with Elliot in the shadows, gripping a post with a vice-like hand. She knew that hand, the feel of it. She then considered Geordie – I know you too . . . from somewhere. Her voice: “I will.” His voice: “I will.” Applause. The fifers played a jolly tune and the newlyweds danced to a clapping rhythm. All danced, the walls resounding, the plank floors shaking. She surrendered to his hand and the world felt safer. Elliot fled. Good riddance. They slept on a bed of hay in the midst of the Company, spooning and nothing else. No place to steal away. No sycamore to shelter.

And a good thing, she now thought, standing in the warm kitchen. A year ago, on Old Pye, could she’ve imagined herself here with a new husband? Where might she be Christmas next year? In London? In a far better flat than she’d ever known? So she hoped. MacEachran would go far, a man of good character – a sergeant’s sash – 1 & 10 per day. . . That he outlast the war . . . Billy didn’t – didn’t make it through the start . . .

She scratched flour off her nose, flour to make Christmas bread. Lemuel Burch, their landlord, allowed them the kitchen this day, and glad to do it, happy to be free from the rebel army from whom he received nothing, not like the Commissary General who paid him for the grenadier company to be lodged in his barns. The war almost over. New Jersey is British once more; Americans here amiable. Indeed, Burch said if the women make it for the household, they could make some for themselves. That’s richness. No wormy meal from the victual ship; Burch had secured better. As he should, he’s paid enough. And what the Company was not provided, they’d have to forage, and from whom would that be but the local farmers. No, better to provide and provide generously, especially this Day, a day for Good Feeling, Generosity, Heartfelt Display. The women thanked him, to which he replied he could do nothing less – God bless the King and the Soldiers of his Country.

At the table, Grace worked a ball of dough dotted with raisins; thank God Burch was neither Puritan or Quaker, they’d be cold in the barn. After a few good slaps, she crowned it with bits cut like holly then glazed it. “How’s that?”

An accommodating nod from Obedience.

Grace thrust her naked arm in the beehive to count ten. She pulled it out at eight shaking it, then scooped the loaves one by one with a paddle and slid them in.

“Gill was a baker,” Obedience said.

“Was he? Must not been a good one to join the Army.”

“But he was. Very exact, to his ruin. If he’d stayed in the trade he would’ve starved or it’d kill him, I think. Then he joined the Service and it did.”

“Was his time, poor man, not the Service,” Grace said. “Safer than on your own. We’re family.”

“Are we?”

“Yes . . . and you’re in it.”

Outside a sweep of sleet and snow, tapping at the window.

“A fine stone house,” Obedience said.

“It is.”

“And to a Common Man.”

Grace shrugged. “America’s rich. Who can fail?”

“They’re all fat.”

They chuckled.

“Money and fat,” said Grace. “Marry an American and be fat. Meats and pies at every meal. Thank God the country’s big. No filling an American belly. And loud. A pulpit voice – that Mr. Burch.”

“I’m loud when I sing. Too loud my father said. Better suited to the company of men –”

The kitchen door banged open as Bess Waddley pushed in with her cap blown back. She trundled to the table, her apron up and weighted with two bottles cradled in her arms. “See what I have.” And she spilled her prize on the marred top. Oranges and lemons.

“What’s the spirits?” Grace asked.

“Brandy,” Bess pronounced with a cunning grin.

“Didn’t steal it, did you?” Obedience asked. “We’re ordered not to loot.”

“Oh, that I should think of it! And the 55th’s going house to house, pulling the goods to the street; the sergeant ordering their women to stand guard with their knives . . . We’ll tap that cider keg, some sugar and cinnamon from the mistress’s cabinet and make a punch.”

“So where’d you lob these?” Graced asked.

“I paid for them.” Obedience and Grace exchanged looks. “I did,” Bess said.

“With what? From whom?”

“A Tory merchant.”

“You haven’t the cash,” Grace said.

“Didn’t pay cash.”

“What did you do?”

“I granted some . . . liberties.”

They covered their mouths and laughed.

“Your man finds out, he’ll murder you,” Grace said.

“He won’t, ‘less you bitches tell him. Weren’t nothing but a finger and a feel. Besides, when did you last taste an orange? We’ll have a Christmas bowl and dance to 12th Night. A toast to ’77 and the rebels undone.”

“We were just speaking of them – how loud they are and fat,” said Obedience.

“Oh, they’re fat,” Bess said. “Look at their daughters, meaty country girls. But not from town, pretty girls come from town. Rebellion comes from town as does all liberal thinking. Ever hear of a country riot? American talk. Loud talk. And everyone – a bloody gun – not one good cudgel. Imagine a rebellion in Cotswold? Foreign enemies you take, but not your own countrymen. Even the good ones, they’ll turn on you like a wild dog. Most are so stupid they don’t know why they’re fighting. Shout a slogan and off they go.”

“Not the loyalists,” Obedience said.

“They were all loyalists in ’63. I hate them.”

Obedience shifted, gripping her hands as if one contended with the other. “I don’t hate them, just the ones in rebellion.”

“They put my man in danger. Let ‘em them go.”

“That would undo the world.” The words jumping out of Grace.

“‘Undo the world’ – always something trying to undo the world. The world ain’t undone so lightly.”

“We’ve an obligation – to the good ones,” Obedience said. “Look at Mr. Burch cantoning us on his property.”

“He’s paid for it.”

“He’s allowing us the use of his kitchen. He’s not paid for that.”

“Do you see any servants?”

“He’s loyal, I can tell.”

“For the moment. It’s ‘God save the King’ when it suits them –

“But the war’s over, mostly over,” Grace said. “Officers in New York renting winter houses, Lord Cornwallis to sail home. New Jersey is British once more. And Howe’s decree – they’re coming through our lines and everyone’s forgiven.”

“If it was us,” Bess said, “we’d be shot dead or on a gallows.”

“Howe can’t hang them all,” Obedience said.

“He could least hang one or two. That’d be entertainment – watch Georgie Wash dangle. Stretch those birds in Congress too for the harm they caused.”

“But Billy’s done well,” Grace said.

“. . . For himself with his Yankee tart,” Bess said.

“He’s done well and we’ve been fortunate,” Grace said.

“Fortunate?” Obedience asked.

“Most fortunate.”

Bess went to the cider keg against the wall and looked down the hall to make sure no one’s coming. She grabbed a pitcher and filled it. “Mr. Burrows not so fortunate; Jack was behind him. I’m still cleaning bits off Jack’s waistcoat. At least it was quick. Some linger for days. The worst sort of end.”

A crinkle of Obedience’s nose – the smell of the sickbay.

“Hospital duty,” Bess said. “Give me a thousand shirts to mend.”

“I’ve not served yet,” Obedience said.

“God keep you from it, as Patient or Nurse.” Bess went to the sugar chest to throw two handfuls in the cider.

“Heat that in this,” Grace said, handing her a cast iron kettle.

“. . . I tended Captain Bourne,” Bess said. “Meer Prig, but in truth, a kindly gentleman – no class distinction with diahorrea and vomit’n. Though not the brightest wick. Not like Leigh. I think he’ll get more men killed . . .”

Again the kitchen door banged open and a lump of blanket and petticoats rolled in; Jaruesha shaking off sleet beading up on the blanket pulled ‘round her head like a wimple. “Aught, it’s ‘pear driech t’dae.” She spotted the pitcher Bess was about to pour in the kettle. “What’s that?” Her eyes brighten and she mugged a rare grin.

“It ain’t ripe yet,” Bess said with an overweening caution. “And with your nose, you go last.”

Jaruesha smiled, a face rarely seen, staring at the pitcher’s neck like a baobhan sith who’d not drunk for weeks. “I should go first maybe to lighten my nature.” She sauntered to the hearth and lifted the lid of a large pot. “It’s nearly boiled out,” she bleated. “dh 'eug Dia e! First good stew and some trusdar can’t mind it!” She turned on Obedience. “It’s you. Who else?” She tromped to the water cask and filled a beaker. “I ain’t using my salt neither. Let her put her own in.”

“What did I do?”

“Aught, Deoghail am fallus bhàrr duine mharbh siadha tiadhan.”

Bess, hand on her hip – “Speak fucking English, Mrs. Tree.”

“What’d she say?” Obedience bridled.

“Best not to know,” Grace said.

“Here,” Bess said, thrusting a brandy bottle into Jaruesha’s hand.

“You, in there!” an elderly man thundered from the hall like a kettle drum. “Obscenity! I hear obscenity!”

“Not us, Mr. Burch,” Bess called, feigning shock.

“Some guttural, Papist tongue –”

He was fat: barrel-chested like a beer keg, porkpie fingers, legs like foremasts, a David returned to the Carrara block. White as white can be with skin like velum. A rose to his cheeks, but all spidery and wilted. And yet spry in his step, so if attacked, he could trounce you the first round.

“I was assured I’d have no trouble. Your captain said Foot Guards were not like common Regulars and their women restrained. Your captain said if any damage occurred to my Property or Harmony, he’d take it out of you. When the rebels held the town, they were animals. I hope his Majesty’s troops conduct themselves better.”

“Our apology, Mr. Burch,” Grace said. “No offense intended. Some are a little coarse, an upshot of campaigning.”

“Curb yourself,” he said, then caught sight of Obedience in a quarter turn as if to hide herself. He looked the way an old man looks, thinking his stare indiscernible, and for a moment young again, the handsome fellow.

“We’re ever so grateful,” Grace said, “for the use of your kitchen . . . and to cook your supper . . . and Pudding.”

“Just this once,” he said, gazing at the line of Obedience’s neck, who lowered her eyes, knowing it.

“Our meal will soon be on and a fine celebration.”

“You’ll celebrate in the barn,” Burch said and then addressed Obedience. “What is your name, madam?”

“Mrs. MacEachran.”

“And Mr. MacEachran?” he was compelled to ask.

“On duty.”

Burch considered. “Mind my house,” and left.

Bess pulled a yellowed pipe from her pocket. “You know what he wants.” With a piece of straw she lit the bowl and blew smoke out her nose. “Best you not be alone,” she said to Obedience.

“That’s ridiculous,” Grace said.

“How he looked at her.”

“He’s old.”

“They’re the worst. Seen his wife? A witchy crone. Has Middlebrook a brothel?”

“Listen to you.”

“Old men are like that,” Obedience said.

“Well, I doubt if that old man is.”

“Why’d he be different?” Bess said, then again to Obedience, “Make him pay you for it.”

“He’s a farmer,” Grace said, “not a gentleman. A Quaker . . . or a Methodist.”

“They’re all dogs.”

“He’ll hear and throw us out.”

“Mrs. MacEachran will smooth it over,” Jaruesha said.

“Probably swives like a Quaker,” Bess said. “‘Time to plough the field. Time to milk the cow. Time to swive the wife.’”

“Least it’d be quick,” Jaruesha said.

“Quick is the young buck,” Bess said.

“Who wants it quick?” Obedience said.

“The Academician,” Bess said.

“The wife who loathes her husband,” Jaruesha said.

“She doesn’t want it – least not from him,” Bess said.

“When she does it, her mind’s in another place,” Obedience said.

“She betrays him in a story,” Jaruesha said.

“And loves him in a story,” Grace said. “We live with our men in a story.”

“When the story is good, the sex is good.”

“Fucking story?” Bess said. “I want cock, not a damn cuddle, best with a stranger, that or braised oxtails with turnips and potatoes in gravy. A good meal sticks and you don’t regret it. Never regretted one yet.”

“And they make you out more than you are . . .” Obedience said. They looked at her.

Bess laughed. “Well, maybe you.” Then to the group – “Here now, tell me: how you can burn for a man one minute, then he’s ‘this worthless son of a bitch’ I’m stuck with. And then the fool looks at you – ‘What did I do?’” They laughed. “‘Stupid bastard, anyone’s better than him . . . Get myself a new lover’ . . .”

“And better to do it before you age.”

“But you’re a woman and saddled with him.”

“The digit,” Bess said, holding up her finger.

“Enough,” Grace scolded.

“You were laughing too,” Jaruesha said.

“It’s Christmas.”

“Christmas – what does that have to do with anything?” Bess said. “Another day beside Sunday to snore through worship . . . and out in the freezing cold. Thank God New Years is not far away.”

“Have you no shame? What kind of Christian are you?”

“I’m not,” Bess silenced them. “I said it, not that you care.”

“What are you then?”

“Enlightened . . .” They laughed. “Life’s harder for a woman. The world’s designed against you. You have to swive with it, or make it think you will for it to give you anything.”

“Who believes that?” Obedience asked.

“You do,” Jaruesha said sharply.

“I do not.”

“You’re a tilt waiting to happen.”

“Well, we know you’re not, Mrs. Tree,” Bess said. “The pleasure in a swive is compensation. We don’t pay for it like men do.”

“You pay for it,” Jaruesha said.

“I never do it unless in love.” Obedience pressured.

“And you’re in love,” Jaruesha said. “Always.”

“You have it backwards, my dear,” Bess said.

Jaruesha scoffed. “Moll Hackabout here.”

“An enlightened woman does it for her pleasure,” Bess said.

“I can’t afford enlightenment,” Grace said. “I’m a soldier’s wife. I need God’s graces.”

“Until a man of title comes along,” Bess said, “and then you become a lady. Or he’s a man so handsome, you hope his heart and purse will match his looks.”

“Either way we get the worst,” Jaruesha said.

“Mrs. Baddeley did well,” Grace said of Henry Clinton’s mistress, “a sergeant’s wife – gives a girl hope – become a lady and get the Vapours. ‘Excuse me your lordship, Lady Waddley’s indispose with the Vapours’.”

“Big talk,” Jaruesha said. “You’re owned like the rest of us.”

“But our Obedience here, she could snare a major, maybe two,” said Bess, “have a salon of her own. Poor MacEachran, he’s doomed.”

“Or his fortune’s made,” Jaruesha said.

“Stop it,” Grace said. “I’m a Christian and this is Christmas, God came to save the world.”

“From what?” Bess said. “When your privates burn, fetch them off. The sin is Avoidance. Until then, that’s all you think of till it’s done. The Church would have you praying and so bridled you’re bout to burst. Your will is gone.”

“And your soul,” Grace said.

“What soul?”

“What about our darling here?” Jaruesha turned to Obedience.

“What about what?” Obedience said.

“What’s your experience?”

“My experience is my business.”

“You’ve got so many comers.”

“Let her be,” Grace said.

“Come on, Obedience,” coaxed Bess. “Just us,” and she frowned at Jaruesha, “Grace and me. How many?”

Obedience stared at them. “Eighteen.”

“You can still keep count,” Jaruesha said.

“My, and not a brat from one of them,” Bess said.

“Not one that we know,” Jaruesha said.

“Do men keep count?” Obedience asked.

“Can they?” Bess chuckled.

“I bet MacEachran can,” Jaruesha said.

“He’s no innocent,” Obedience said.

“And you’re the last . . . to the death of him.”

“What do you mean?”

“You love him?”

“Stop it,” Grace said.

“Cupid’s arrow,” Bess said.

“I said: are you in love?”

“What do you care?”

“Enough, Mrs. Tree,” Grace interceded.

“I think MacEachran’s saved you from the Devil, but he may have you yet. Why didn’t you go back to where you belong?”

“What’s that in there?” Burch’s voice shouted from down the hall. “I’ll not have it!” And charged back into the kitchen. “What’s the matter with you?” he said to a red-faced Obedience. “Your name again?”

“MacEachran.”

“Out, all of you! Back to the barn!”

******************

Lemuel Burch presided at Table in an umber suit of middling quality. Save for the waistcoat, a burst of Chinese Red, brocaded with oak leaves and gold taping. A garish thing once a Fashion, expressing of him what he could not express. How festive, in his limited way. He wore it for his Wife and Children, and honoured Guests – the man he once was: liberal, extensive, of great compass, to don it made him feel blessed and Life not so chafing. That the Rebels hadn’t taken it. God knows, they took everything else. A gang of thieves: not quite soldiers, not quite men. And such anger. Illogical. Misdirected. Thank Heaven the officers were rational persons or there’d been a riot; that they hang a private man everyday as a precautionary. God knows any private would gladly do them. The Mob . . . his Majesty’s soldiers were not much better, some dogs . . . and their foul women . . . he looked the way an old man looks . . . But he’s a Patriot and would assist his Majesty’s troops. The bill for freedom. He smiled at Captain Leigh.

Charles Leigh, young, dark and twenty-eight, the very figure of a Household Officer. Ensign at sixteen. Captain at twenty-two. Surely to rise high in spite of all privilege, which generally made one a profligate. A nod to his host, surveying such a waistcoat. Yet not too long and a quick turn to acknowledge Mrs. Burch, a surprisingly attractive woman for her age without the jowls of most matrons and not a’tall ‘Witchy’.

“Captain Leigh, are you married, sir?” Lemuel Burch to the point, so American.

Frances Barbara Charolette neé . . . Byron Leigh. He could not help but smile. “I am, sir.” A crazy pack – Byrons. What beauty and money’ll get you, and F.B.C. as pretty as you please with Daddy, a fine admiral, and a brother in the Coldstream, Mad Jack, a drinker and scrapper, itching for cash. “Indeed I am.”

“Very good.” He nodded to his wife, to which she agreed: a rich and considerate young Gentleman sitting at their table, that it be so with their sons where they’re billeted, somewhere off with Skinner’s Corps; little did they know of their children’s military animus. Of soldiers, their only experience was of Washington’s men and now these poor wretches come into Middlebrook haggard from chasing them. Our sons, they thought, our good, brave sons. The Regulars had not eaten or slept in days. “Lend them the kitchen,” Mrs. Burch said against her husband’s better judgement. “Just this night, Christmas. They’ve suffered . . . and they can make our supper too.”

“Find you the rebels a capable adversary, Captain Leigh?”

“They do present a challenge, sir. They run like the wind. Some of their regiments are surprisingly good and their marksmen can be quite dangerous. But they are, for the most part, disorderly.”

“I shall never forget the ones quartered here,” said Ina Burch, “horrid creatures, ‘specially the New Englanders. I’d rather keep horses in my house. Where they from, Mr. Burch?”

“New Hampshire, my dear.”

“New Hampshire – another world. Where is it? What is it?”

Burch rolled his eyes. “The most New England of New Englanders, Captain Leigh.”

“And no respect for anything New Jersey,” Ina Burch said. “Never could humanity sink so low.” In her mind, a puffy-eyed creature, like a pumpkin face pushed in.

“You find the action exhilarating?” Burch asked.

“It can be hot,” Leigh said. “A sad war, Mr. Burch: we know a number of their officers and at one time served together; Charles Lee and my father are friends.”

Burch nodded. “A sad war, yes – to fight against your countrymen. All this conviction; my own sons caught up. I think there’s no greater sin than that of Conviction. And all this damn pamphleteering as if any fool has something to say . . . Crackpots. Politicos. Greedy syndicates. Intellectuals with their fancy talk . . . Heaven save us from fanatics whatever their stripe. Fanaticism, not money, is the root of all evil. A good balance sheet makes the world right. Would we be here if we had one in ’63?”

“Would we be here if the militias could fight in ‘54?” Leigh said hastily.

Burch sputtered and blinked all piebald.

“Mr. Burch was . . .”

“Oh – I –”

Burch with a conciliatory hand. “No need, young man. ‘Tis the same rascals you contend with now.”

“. . . And they haven’t learned their lesson.”

“Have you suffered much loss?”

“Any loss is hard on the men.”

“You feel for them, Captain Leigh,” Burch remarked.

“Indeed. Their good health is my responsibility.”

“I did not realize an officer showed affection,” Mrs. Burch said.

“Not affection, ma’am – Care – in punishment and reward. It brings out the best in them.

A few blackguards, but most are decent souls. Brave and noble fellows in their way. Hard for Civilians to fathom, but the Service is a Country of its own. Even more so the Navy, if I may say . . . Take away the Coat, they are someone’s son far from home.”

“But as you say, a Country all its Own.”

“Indeed sir.”

“Well, at least we can give these Sons some warmth this Night,” Mrs. Burch said.

“Yes ma’am and a warm one you’ve given me.” Leigh raised his glass. “A toast to you, and Mr. Burch.” And he announced, “I retire to New York for the Holiday next.”

“You leave your company alone?” Burch voiced with concern.

“Not to worry, the sergeants are here and I shall return.” – in two months, which he dare not mention.

“Well,” Burch with his glass empty. “As you say – noble fellows.”

“Sergeant Webb will be at your service night and day.”

“And your women, who watches over them?”

“Why, their husbands of course . . . and a corporal.”

“A colourful lot. Quite . . . sturdy. Campaigning must make them so, I imagine. Are they manageable?”

“Quite manageable,” Leigh said. “Some are coarser than others, but of good character.”

“I noticed one is rather pretty – for an army wife,” Burch said. “Rust coloured hair and hazel eyes.”

“Mrs. MacEachran.”

“Such looks must be hard for the men, especially her husband.”

“The army is the army, sir.”

“I’ve noticed her too,” Mrs. Burch said. “Something melancholy.”

“Yes, ma’am. Mrs. MacEachran has had her time,” said Leigh with surprising empathy. “She’s green to the Service and came over with her new husband who died on the voyage. Private MacEachran married her so she would not have to rely on the pension and be shipped back on her own.”

“In the kitchen this afternoon, the other women were handling her badly. I feared there’d be a row. I sent her out to her husband.”

“Poor dear,” Mrs. Burch said.

“As I said, she’s green and needs a bit of hazing, but I assure you this will not happen again.”

“Lucky fellow, Private MacEachran,” Burch said. “. . . As much luck as you can have in a tent with five other fellows.”

“Mr. Burch,” his wife scolded.

Burch refilled his glass. “Mrs. Burch was a beautiful young girl. I was speechless when I courted her.”

“Burch, in those days, was trim,” she said.

“MacEachran is a good man,” Leigh said. “Mrs. MacEachran did well.”

Burch downed his glass in a gulp. He filled it again and toast. “A night for goodwill and charity.”

******************

Burch, in a banyan gaudy as his waistcoat, held the lamp high in the sleety snow as he and his Negro chattel tromped over the slushy yard to his main barn. “Mind you,” he said to the ‘boys’ as they pushed wheelbarrows. In each a keg big as an old boar. The temperature was dropping, damn cold, and good for a strong, black Porter. Porter is what he called it, though it’s beer gone off . . . well, not completely gone off, just a bit sour, but ain’t all Porter sour? Not that they’d know . . . They ain’t pay’n for it. Webb and Crookshank met him at the door. What’s Christmas without Inebriation? The Good Lord sanctioned it. God knows the Rebels are doing the same wherever their miserable accommodations. And Burch, himself, tipsy as what could account for his generous heart. That they have a ‘drunk’ and fuck on this Happy Christmas Night – let Virgo ascend the Chart, small recompense for their Service.

The barn was warm and very crowded – the Men and their Wives, the majority acquired along the way, triple the original number, and some, like Magick, just appeared, indeed that very Day. . . And unto certain Shepherds the blessed Angels came . . . Oh, Webb, Meadows and Crookshank have ‘em well in hand . . . And there was Musick, a hot fiddle jig. They danced. Straw pushed aside and space cleared. They smoked. They gambled. And here came Burch, the Man of great Compass with his kegs of Porter beer.

“Have a care!” Webb’s parade ground voice grabbing them by the neck. “Have a Care!”

Not a peep or a move. “Incline your attention to Mr. Burch, our Landlord and tonight, our Benefactor.”

“Good evening, you men,” Burch said, finding himself somewhat sheepish. They looked at him. Tough men. Gristle leanness. Tough faces. Rough hands, death in those hands. He wanted to drop the beer and begone. “You are faring well?” They nodded. “Thank you for your good service.” Burch turned to the Negroes. When they saw the kegs they cheered. “Some bitters to keep you warm,” he cried relieved. “Happy Christmas.” Again they cheered.

“MacEachran,” Crookshank called and motioned him over. “Mrs. MacEachran too.”

****************

With a lamp in hand, Burch pulled up a trap door cut into the kitchen’s wide pine flooring. “– was gonna put you in the attic.” A hint of a slur and he measured of Obedience with heavy eyes. Light dappled the walls from the fire dying in the hearth, the room turned cold. Burch passed Obedience the lantern, hoping he might touch her hand. “But this’in’s dry and private, and not so chill.” They stared at him. “Go on, go on,” he said, “less you wish to sleep in the barn with a ‘hundred other fellows watching everythin’ ye do . . .” He’d watch ‘em and pay for the pleasure, and as quiet as a mouse, might press his ear to the floor.

“Thank ye, sir,” Geordie said befuddled.

“You’re too kind, Mr. Burch,” Obedience said, her voice like silk unlike the grate of Army Women.

“Well,” he paused, “. . . this of all nights, why not Charity?” And he turned his gaze from her. “There’s an ample supply of straw to soften the floor. I’ve additional blankets . . .”

“But why, sir?” Geordie asked.

“Pat-tri-otic feeling,” he jibed, but then in shame, he said, “You’re someone’s children.”

****************

The cellar, an unwavering cool whatever the season: in summer a mild temp, in winter like a Venereal morn – just right when any touch of sun is warm and under a blanket cozy. It’s deeper than they expected, the planks a good foot above their heads. On the bare earth floor a bed of straw, which Geordie worked like a cardinal at his nest. Obedience, watchful, clasped the blankets and lamp, the light flickering.

“Are you cold?” He cloaked her with his regimental.

And on cue she reclined with him. An awkwardness. Not yet Lovers. Not true Man and Wife. Strangers. Though not with the strangers’ romp, throwing off clothes in a rush. In that rush she could close her eyes. True, they once fucked. Fucked – the word. Now, they saw each other. No artifice. No hiding. Her hand glided over his fly. She do – a Ritual, one button at a time ‘til nothing’s left but his shirt and what stuck out from under it. His turn – peeling ‘way her armour. And there they were, exposed. Their forms. Their beauty. A mole above her bush, the way his erection arcs.

The cellar grew warm, the straw crackling as he moved over her. In his eyes, she searched for his heart. A good man? She put him in, and they stopped dead still, staring at each other.

A bead of sweat rolled down her rump. A kiss . . . They started, though wanting to hold back.

She grabbed him, her eyes pinched, chasing – a look she often pantomimed – but desperate now to let go. Not that she has not loved. Not that she has not been loved. But the look so sad. He mustn’t see. They rolled. She leaned forward, head past his shoulders, their bodies churning. Then it took her. And she’s lost – upon him, upon . . . him. She seized up and crushed down . . . Then still. Still. Still.

He gushed.

She opened her eyes and laughed. Covered him with kisses.

And he wept.