S T A V E

XV

November, 1776

“I cannot serve under him another day,” Henry Clinton fumed, his nose wrinkling.

The room ponged of tar and fat and funk to heighten his irritation; Yankee households have a smell, ‘specially the rich, owed, no doubt, to the American Practice. So the well-bred Englishman might think, though English manors the same to a lesser degree; a Nabob perfumes his Negers don’t ye know, though they be only one or two – don’t buy ‘em for a Plantation, but for the Mistress and Children and are every bit of the family, may teach ‘em Languages and Art, set ‘em on tour. Virtuosos, not mules – he ain’t a Slave but a Liverpudlian. Still, Clinton should be used to it – nappy American sweat, having grown up ‘round the Markets, even as a manservant stood at the door. Invisible Man, incapable of listening in his patched trowsers, open shirt and brass collar. He come with the house, a fine Tory house, him and ten others, two hundred apiece in Yankee dollars. A stable. Ain’t that wealth? Though they don’t know not to mix House with Labour; Americans – they stretch ’em every inch – that Puritan Ethic . . .

“I’d rather command three companies by myself than hold my post as I’ve done in his army.” Clinton stares at the Boy as if looking at the ceiling.

Charles, Lord Cornwallis, the most sanguine of the High Command, a strategic finger to the base of his nose, bobbed his head in apparent agreement. The room had a must. Wet dog. Them? They’d come from the Field – constant campaigning. Since the great Fire, Billy pushed Washington north. They brawl. Billy brawls actually. Washington scurries behind rocks and trees, and Billy, seemingly on the cusp of victory, lets him off.

What the Hell’s he thinking? He’s got a plan, say some. Got a plan? Finish it! Exasperated line officers take to direct fighting, shooting like the Private Men, while their bully boys, tougher, better, win the day – Hubris over Discipline. Cowards – the Enemy. Let the Savages have ‘em – would’ve had ‘em in ’59 if not for Wolfe . . . and Billy scaling the Heights of Guan. And here Harry Clinton, devising plans, which Billy considers artificiality.

But Cornwallis knew, as did other Senior men, Billy’s intentions. After all, he and Lord Richard are the Peace Commissioners. With whom may one reconcile if the Opponent’s dead? “Something from the Bible, I think,” Billy once said, (Scripture’s always good for authority) maybe at a faro table or between bumpers of gin, “Chasten not your son too severely lest he lose heart and . . . e r. . . run away – something like that . . .”

“I’ve tried,” Clinton said, “really tried to assist him. He claims every prize, takes all credit – by my hand.”

Cornwallis restrained a smile.

So did the manservant, his poxy skin shining. Never did a placid face bristle such affect.

“If he’d listened to me, this would long be over . . . He hates me.”

“He doesn’t hate you.”

He hates you – the manservant’s lip tensing.

“Jealous then.”

“Billy?”

“Maybe not – too dull – that obtuse grin. He’s over his head. If only it were my grandmamma fucked German Georgie . . . Well, he doesn’t care for me, it’s clear. Doesn’t care for what he doesn’t understand – all those fussy tactics. We’re ‘Germans’, You and Me. Too bad a little German did not leak down in him. An incorrigible fellow. How do you keep peace with him? ” Clinton tossed up his hands before he could answer. “Knight of the Bath – for my plan.”

Cornwallis shrugged.

The manservant’s shoulder – an imperceptible lift.

“I’m such a bitch,” Clinton sighed (the Boy – a dart of the eyes to Clinton’s fly). “You know this could’ve ended on Long Island . . . I would’ve ordered it if I was in command.”

“Frustrating,” Cornwallis acknowledged. “He has his reasons though, but still, a brilliant piece of work – Long Island. I know it was you, Harry. We all know. (Me too – the Boy) Even Billy. Have patience. They’re unraveling. Besides, we’re Soldiers.” He clapped Clinton’s back. “It keeps us in the game.”

“Doesn’t it bother you to see the army ill-used?”

“It would bother me to have myself ill-used – in some rearguard Action.”

“Well, we know the Truth – But will History?”

“History? . . . Proclivity’s invention! Gospel Keepers. Armchair Generals. Writ by the Winners to justify their Victories, and again by the Losers to mollify their loss. Exaggeratists and Liars. We’re damn Novelists with intersecting arcs. Truth ain’t facts, it’s stories . . .” And Cornwallis with his weedy eye reflecting in the manservant’s shiny brass collar, asked, “What you think, Boy?”

*********************

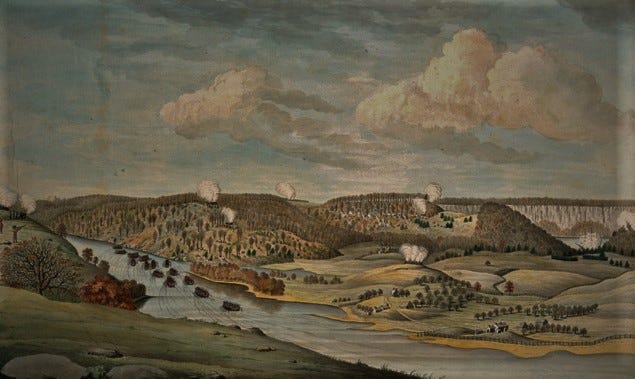

Predawn on the woody heights sloping down the Kingsbridge. Frost bristling the hoary grass, brown desiccated leaves and trees bare to the top of their branches. A dust of light snow. Salmon coloured sky. The air with a snap. Marvelous day for Battle. Saturday, a breath before the Sabbath. One must smile. They march, the Guards and Light Infantry, to the banks of the Harlem. Canteens, blanket rolls and haversacks with one day’s Ration. The flatboats should be along. They wait – what soldiers do. To them it’s not waiting, but slow, dense time, a finite world drawing to its end: unnerving, tense, charged. They’re told little. Whatever it is, they’ll see. Fort Washington – they know that much. Suppose to be impregnable. They smoke though they’re not supposed to. Will they go? Nothing’s certain though everyone’s in place or trying to get there. Where are the Flatboats? . . . Home . . . To go home . . . Don’t think it . . . They’ll come . . . And shortly someone’s dead . . . Don’t think it. They breathe a warm living breath that vaporizes and vanishes. At the Ready – flints knapped, locks oiled, barrels cleaned bright and shining – let ’em see it, they know what that means . . . Hands sweaty. Hearing keen. Scared is not a feeling. Scared’s what they are . . . Does he look scared? Does he look scared? And me? Hell no, done this before – a ball’s lovely zip – music. The Almighty . . . The pretty dawn . . . Lucky Odds . . . Who dies on a pretty dawn? The other man, God’s picked them out – Hessians and Waldeckers just off the boat – the frontal assault, the Honour, the poor by-blows. A climb to Manhattan’s highest point, Fort Washington at the top, with a sheer two hundred foot drop to the Hudson. Big fort, four acres – like Georgie’s head . . . Bristling outer works. Defensive ditches. Bloody as Bunker’s Hill. Bloodier? . . . Where’s the bloody boats? Maybe we won’t go.

The siege should last a month – Colonel Magaw, the fort’s commander – slow fighting every foot. Chew them up. Bold talk for a man surrounded: three thousand Hessians on his front at Kingsbridge; grenadiers, the 33rd, Guards and Light Bobs to attack up Laurel Hill; Lord Percy attacking from the south, the 42nd to his far right as a faint. An assault from three sides, with a twenty gun battery on the Bronx hills and the frigate, Pearl in the Hudson hammering with her 12-pounders. Still, a number of failed sorties from the days before bolstered Rebel confidence. “Surrender and receive the Courtesies of War,” Howe’s ultimatum delivered by Lieutenant Colonel Patterson. “I shall never surrender,” Magaw’s reply, “and will hold to the last man.”

“No quarter shall be given.” “None shall be asked.”

Now they wait for the flatboats and high tide. Cannon fire sounds in the distance.

“That’s a tune,” said Willcock with a stammer.

Geordie with a reflexive nod.

Before them flowed the Harlem into the gorge between the Bronx and Harlem Heights, a shadowy place the sun could not catch until late morning – like a waiting maw to their eyes. Then flashes from the Bronx heights. The report shook them. “Christ!” “Goddamn!” And frightened laughter. Shot flying like comets into Laurel Hill. Raised their fists and cheered. “Do it!” they shouted. Blasts like a feu de joie and in the canyon a fog of sulfur. And weary smiles with heads bobbing. Keep firing. They look about – fifteen hundred men, good company. Élan will protect them. And put them in Danger. They’ll be the first in and drive up the hill through the outer defences, if any are left. That none be left. Somewhere down the river the enemy waited, faceless and vicious, like foxes in their dens in want of eradication.

“Hessians – ” Willcock said. “All their bloody hymns –” They’d heard them singing as they had marched over Kingsbridge. Goddamn Lutherans as if the Almighty don’t know what He’s about – always have to remind Him –

They shivered. Geordie more than most, he thought. The boats – don’t let them come.

“Nothing undoes me like bloody hymns,” Willcock said.

“The rebels sing them,” Tim said.

“And weep in their grog,” Dan Burrows said.

“And pick at their poxy scabs.”

“. . . fucking hymns . . .”

“You’d sing too: Billy’s going to blood them good,” Harrison said, “attacking the front.”

“And what are we going to do?” Tim quipped.

“Stomp their guts,” Willcock said.

“Hear! Hear!”

“Fucking bowsies,” Willcock spat. “Fucking Yankee Doodles.” He sang: “Yankee Doodle pissed himself hiding behind a railing. Up came the Guards and stomped his guts and gave him an impaling . . .”

Laughter. The squad sang:

Yankee Doodle pissed himself

hiding behind a railing.

Up came the Guards and stomped his guts

and gave him an impaling.

Yankee Doodle can’t keep it up,

Yankee Doodle Dandy,

mind the music and the step,

and with cock in hand your randy.

“Yankee Doodle got so drunk fearing next day’s battle. He swived his horse and saddled his wife and rode her into battle . . .”

Yankee Doodle can’t keep it up,

Yankee Doodle Dandy,

mind the music and the step,

and with cock in hand you’re randy.

“Doodle went to Holy Ground, looking for some pleasure. The doxy cried, ‘I can’t, my dear, it’s of so little measure.’”

Yankee Doodle can’t keep it up,

Yankee Doodle Dandy,

mind the music and the step,

and with cock in hand your randy.

“Yankee Doodle took up his arms, demanding liberation. But when he sees the Bloodybacks, he’s filled with hesitation.”

Yankee Doodle can’t keep it up,

Yankee Doodle Dandy,

mind the music and the step,

and with cock in hand your randy.

Indulge it – the commanders. Such is the way with men. Whip them up. Win the day and retire to the gaming tables and New York girls and bottles of Claret if to be had. Then Madera. When that’s gone – rum and gin . . . What’s a Yankee bullet compared to gin? Gin’s twice the danger – Captain Bourne dead and Madan on his sickbed – taken down by black-market gin after exhausting all proper drink. So potted, they noticed not the taint in a cold haddock-oyster pie. Now a new captain of the Guards Grenadiers, Captain Leigh of 7th Company, the type that’ll get you killed – him and Colonel Osborn over a hundred scrappy orphans.

So they sang, except Elliot, his gray eyes fixed on the river, one tune then another. It bought an ease as cannon fire cracked in the distance. Ten men, then twenty, then a hundred, 1st Battalion, 2nd Battalion – the Brigade. It jumped to the light infantry, then all 1500 singing, a great sound to the chorus of cannon, voices echoing off the granite knolls.

Courage, boys, 'tis one to ten,

But we return all gentlemen

All gentlemen as well as they,

Over the hills and far away.

Over the Hills and O'er the Main,

To Flanders, Portugal and Spain,

King George commands and we'll obey

Over the Hills and far away.

The boats came, two hours late, fighting the low tide that uncovered a maze of sunken branches in the connecting Spuyten Creek. The entire assault delayed: Hessians waiting, Lord Percy waiting, the 42nd waiting. The Rebels too, dug in, prepared.

The Lights board first, fifty men per boat, crammed so tight they can hardly move. An hour to pull away so the Guards can take their turn; the grenadier company needing two boats, Captain Leigh in the first and Osborn in the second. They pushed into the river, the water like glass. How pleasant. Beyond Kingsbridge, musketry reports and the high, sharp crack of rifle fire.

The heights rose on both sides like great hugging arms as the flotilla rowed in. Twenty minutes of gentle boating. Go, go, go, each man thinking. The woods on their right – and they can do nothing. Underbrush. Placid trees. The hill a carpet of autumn leaves. Nothing’s there. Go, go, go. A flash. Another. Then the sound wave to knock them over. A black blur with a fiery corona. The water cracks. Geysers. Then the sulfur cloud churning, tumbling. Men shout. Rebel cannon thunder again. The shot screams. British batteries reply on the rise to their left.

Geordie’s heart pounding. He stares at his thumb strangling his firelock, the skin marble. The last thing he sees? Cannon balls tear up the trees on Laurel Hill, the shock ringing against the granite outcrops. Ahead a boat of Light Bobs and a blurring streak. Firelocks, wood splinters, sheared red cloth pitch into the air. The boat disintegrates.

“Pull!” the midshipmen in Geordie’s boat cries. “Pull!”

From behind some scrub a company of Rebels pop up and volley into the flotilla. Light Bobs collapse over the gunwales. Shouts, not war cries. Those that can, fire back.

“Pull!”

“Steady!”

“Pull!”

Another volley cracks from the bank; the Lights receive the worst of it, but the grenadier company’s coming into range. The sailors drop and hide. The Light Bobs, cursing, take up the oars.

“Pull, ye sons-a-bitches!”

Smoke – a merciful camouflage. Still the Rebels volley.

The flotilla pulls ashore, the Light Bobs hit the bank. The enemy retreats up the bluffs with a running fire. Then the Guards’ boats heave-to. The grenadiers form a hasty line and Osborn moves them forward as other flatboats pull ashore. Thick forest masks the hill, shrouding its steepness; they slip and fall on the uneven ground.

Geordie, his firelock sloped, huffs and puffs ascending the grade. Gunfire sounds to his front. Musket balls whiz past him. He steps over a splintered tree where a cannon ball has lodged. To his left a loud crack as a bullet cuts a branch. A ball clips another. Geordie’s thighs burn. Sweat soaks his face. The hillside echoes. The rebel position comes into view. Militiamen pop off rounds from behind a stone and wood barrier. Geordie sees their civilian dress, a frenzy of firing and loading behind their little stone wall. A sharp zip past his ear. He touches it. What’s this? What’s this? Blood coats his fingers. Down the line John Waddley and Dan Burrows eight paces to his right. Burrows’ forehead bursts, flecking Waddley with pieces, while Burrows flops. Geordie stumbles. A ball takes his hatt-cap away. His cartridge box jolts with a thwack. He turns and there’s Tim behind him, eyes filled with murder.

They come up to a company of Light Bobs firing under cover of trees, some kneeling, some prone, some standing in defiance. Their few riflemen take careful aim, their contract rifles with the loudest report.

A toot from Osborn’s whistle. The grenadier company halts. Then three quick whistles – commence firing.

Geordie snaps his firelock upright, pulls the frizen cover, full-cocks the hammer. He presents and sights down his handmade groove to the bayonet lug. There – a rebel sticks up his head. Geordie fires. Flash. Kick. Smoke. Behind him – Tim’s musket barrel inches from his head. A blast. Geordie doesn’t hear, his heart a gallop as he plucks a cartridge, rips it open with his teeth, dumps powder, ball and paper down the barrel, rams it, aims, fires . . . Does it again.

He fires. Tim fires. He fires. No spark – “Goddamn it!” Flint’s gone dull. Tree limbs being clipped. Tree bark being splintered. Geordie picking through the box pocket for a new flint. “Goddamn it!” Ears ringing. Smoke so thick. Leigh blowing his whistle. Geordie sets a new flint. Resumes firing. Osborn and Leigh blowing whistles. Leigh shouting, his hand cutting the air. Blowing the whistle again – a long shrill blast. In the cacophony a shouted word – “ . . . Fix . . .” Geordie, presses behind a tree, pulls his bayonet. Behind him, Tim, pressed against his back. Osborn and Leigh stand out in the open and thrust their fists in the air. One quick toot followed by one long whistle. The platoons form close order.

A Rebel officer with a sword stands up from behind the barrier, defying the grenadiers and urging his men to hold fast; on the wall bloody heads and shoulders slumped against the logs. Leigh, profuse with sweat, snaps his fusil level and fires. Still the officer stands, sharpening his men. Near Leigh’s foot, a contract rifle of a fallen light infantryman. He grabs the piece and shoots. The ball pops the rebel’s chest and he tumbles over the barrier. His troops freeze.

“Charge bayonets,” Osborn shouts. Already the Light Bobs rush the wall. “Skin the hounds!”

The militia gives a ragged volley, the grenadiers advance at a run. They hurtle the wall, bayonets rattling. Leigh screaming. The men screaming. The militia scatters, firing as they flee. The grenadiers cry: “Here! Here!” “Get him!” “That one! That one!” “On your right!” “Stick that bastard! Stick him!”

Geordie spots a rebel with a bleeding leg. Catching his watery eyes, the man bolts with a broken stride and Geordie after him. The man, whining, trips and Geordie puts the blade through his leg. The rebel shrieks and enraged Geordie jams him above the groin. He screams again and again, and Geordie, his face twisted, skewers him through the liver. A reek of bile. The rusty stink of blood. The rebel tries to crawl. Tim rushes up and impales him through the shoulder. More gather round: Harrison, Willcock – stabbing. Four violins: Allegro – L'estro armonico.

Out the corner of Geordie’s eye, a Light Bob puts his rifle to a rebel’s ear and shoots away his head.

Colonel Osborn blows his whistle. The squads are strewn throughout the woods. Other companies press forward pell-mell. “Reform! Reform!” Leigh cries, but no assembling them. Down on his right, Colonel Martin and the Light Company in the same scattered mess. Sergeants and corporals take the lead as Guards and Light Bobs mix in ragged order across a thousand yard front. Companies on the far flanks not yet engaged proceed smartly.

Geordie, bareheaded, shirt and coat collar bloody, advances surrounded by his fellows. Up ahead he sees the broad frame of Elliot, blood streaming off his bayonet. He advances on his own.

They walk, bayonets charged, the ground open. In the distance, gunfire rings on both their left and right. Within an hour they see Fort Washington on the adjacent hilltop, ramparts bursting with plumes of smoke; Lord Percy driving the Continentals onto the light infantry coming on their flanks.

Two miles north, the Germans stall as rifle and cannon fire pin them on the rock face. Hand over hand they climb, stealing behind outcrops no bigger than themselves. Hats fly. Heads fly. Trees rent from cannon shot. The air animated.

American rifles flag, clogged with spent wadding. The Hessians climb, a slow hand over hand, officers demanding order, a redoubt before them. Jagers bring their rifles to bear and up come the grenadiers, many bareheaded. Grapeshot splinters their ranks – a fright when hit – cuts a man in two – bloody meat, little left that’s human. Worse for those who see it. The dead themselves don’t care. Still they come and the Yankee gunners meet them: hand spikes, musket butts and shovels, the Germans, in their fine lace and garrison curls close with swords; they scream and take heads – slaughtering pigs, it comes natural. How the pigs squeal and run. They’ll not chase. No English Gallop. Just the drum’s cadence. But seeing the Enemy’s backside and their own shattered dead, they want to run, hunt them like dogs. Americans – devils, animals. Kill them all.

Percy and Cornwallis push the outer defences. Company by company, the Americans collapse. The musketry falls silent and the impregnable fort waits to fall. Up the rocky hill advances a German officer with a white flag accompanied by a single drummer, beating Parley.

“Shoot him!” Magaw orders from the ramparts. “Give them our answer and shoot the bastard! We stand to the last! Shoot him!”

They fire, reports echoing off the walls, but the Hessian strides up as if Michael the Archangel covers him. Cease-fire, a deflated Magaw orders. Captain Hohenstein, in an insulting and intentional broken English, informs that if the siege continues, every defender would be put to death, much to the Hessians’ pleasure.

Magaw looks to Fort Lee across the Hudson; dusk in another two hours. They could escape then.

“I will need time to confer with my staff,” Magaw said. “We will need at least six hours.”

“I give you thirty minutes.”

“Four hours,” Magaw bargained.

“Thirty minutes or all are dead.”

Magaw appears at the gate after the half-hour. “What terms?”

“You may live,” Hohenstein belittles.

“I demand the Courtesies of War.”

Hohenstein sneers.

“I demand my men retain all their personal effects.

Magaw’s clothes and Hohenstein’s contemptuous chuckle. “Agreed.”

A gauntlet forms through which the captured pass. A gauntlet for punishment. The British serve as rear guard. From inside the walls, a melancholy tune, like a maid might sing when brokenhearted. The gate opens and the Rebels begin to pass. The British gape. The Germans laugh. Vagabonds. Scarecrows. Half-naked boys. Old men. Coloured – slave and free. Virginia backwoodsmen with few teeth. Innocuous. Insignificant. Void of all danger.

“This? This?” Willcock exclaimed. “Grandfathers and Negers?”

The Hessians strip them. No promises to traitors. Switch them with ramrods. Kick them.

“Bless you my boys,” Willcock cries, “my fucking German friends, my fucking Brothers in Arms.”

“Sergeant,” Leigh says, “arrest that scoundrel.”

Sergeant Crookshank spears an elbow in Willcock’s diaphragm and the Germans continue the humiliation, the Yankees marching naked.

“Is this necessary, General Von Knyphausen?” Lord Percy says.

The old commander shrugs. “Plunder is honourable. Your men are no different. Our wives will weep for dead husbands and in turn will starve. The rebels could have surrendered with none of this loss. What do you wish me to say to men come over the ocean to die so far from home?”

“General Howe wishes to reconcile with these people,” Cornwallis adds. “We must win them back. They are, after all, our countrymen.”

“Not these here. They are traitors. Let him reconcile with those who lay down their arms. I would insult my men to demand they treat kindly those wishing their deaths. You would not have me insult my men?”

“No general,” says Lord Percy, “we would not.”

“It is an order I will not give.”

“No, general,” Cornwallis says.

“Then it is out of my hands and into yours. They are, after all, your countrymen.”

The British circumvent and direct the prisoners through their lines; they receive no better.

******************

Cornwallis laughed. “Withdrawal?” he said of Fort Lee. “They buggered out like scared rabbits.”

“The best kind of war,” said Howe with satisfaction, turning to Henry Clinton. “Winning without a battle.” And Clinton with a forced smile as if a piss spot on his fly.

“His army’s in shambles,” Cornwallis said. “Their General Putnam wanders about New Jersey, pining for the days of Bunker Hill. He proclaims the rebellion lost. Our agents inform that rebel enlistments are up. Everyone’s leaving. There’ll be no army by the end of the year.”

“Well,” Billy said, “with Mr. Washington in tatters, we can attend to greater concerns – Lord Howe’s winter port.” He stepped to a Claw-and-Ball foot Chippendale pulled out from the wall with the leaves extended and charts strewn on its patchy wax surface. “We know, especially you, Harry, that New York harbour turns icy in the winter. I propose we secure Newport for Lord Howe. What’d you say, Harry?” having a look like Father Christmas. “Six thousand under your command – that enough for you?”

“More than adequate,” Clinton said complacently. “No Rebel force in Rhode Island.” But his eyes then lit with a child’s compulsion and stared at the maps. “But with your permission, I know a way to make such action unnecessary.”

“Unnecessary?” Here we go . . . “The plan is – Lord Richard needs an ice-free harbour. We haven’t much time before winter hems us in. It is the American Secretary’s wish . . . it is his order you invest Newport . . . It is . . . his War: his Majesty – Captain General and Lord Germaine the Architect of Strategy.” A trump card, like a lawyer quoting Contract that one’s never seen; truth be told, he had great discretion regarding strategy. “Next spring, General Carlton, that’ll set Harry off, is to thrust down from Canada and strike along the Mohawk while our Atlantic Army moves up the Hudson to meet him. You are to cut New England in half from your base in Newport. That is the plan. It is agreed.”

“But, I propose –” He cannot help but speak, he must speak or it’ll burst out of him “– we can take Newport no more than two weeks later than scheduled. And if it works, Lord Howe will not need a winter port and New England will be made irrelevant.”

“And what?” Howe asked, already exhausted.

Clinton shuffled the charts. “Give me six thousand to take Philadelphia.”

“No.”

No? The man said No? Just like that?

Admiral Howe shook his head in support of his brother.

“Philadelphia comes after New England,” Billy said.

Clinton gobsmacked and turned to Cornwallis who stood like an invisible man. “Please reconsider,” Clinton entreated. “If I embarked my six thousand tomorrow, I could take Philadelphia by week’s end. Even if Washington tries to oppose me, he would have to divide his disintegrating force between Delaware and the Chesapeake; he’d have no way of knowing our route. Our agents in Philadelphia say there’s no force to oppose us. It’d be as easy as taking Newport with a greater advantage – the rebellion’s end.”

“The rebellion is over. We’ve mapped out a plan,” Howe said.

Clinton tugged on his fingers. “Then have Lord Howe put me a shore on the Jersey coast.

Have Charles push Washington from Fort Lee and I can come up behind him in a pincer. We capture the Continental Army and then march into Philadelphia at our leisure. What could be simpler? And then, what need have we for Newport at all? Lord Richard can station anywhere. He could send most of them home for that matter.”

Howe weighed his next words. “Sir Henry, Lord Howe and I have our reasons.”

“Is it not the Cabinet’s intention to win a swift victory to prevent another global war?” Clinton pointedly.

“We have our reasons.”

I know your reason, Clinton bit back the words. So you can swive your Yankee wench, referring to Howe’s mistress, Elizabeth Loring, the wife of a Boston Loyalist now on Howe’s staff.

“Though we’ve plans for New Jersey,” Howe continued. “Since the forts fell sooner than expected, this gives an opportunity to peel off the colonies one at a time. New Jersey, for that matter, is no longer part of the rebellion. Pennsylvania is about to withdraw. By reclaiming these colonies with a fair and gentle hand, the Americans will pick up the Rebel leaders and toss them into the sea . . . I do appreciate your enthusiasm, but the current plan is working and is best for all concerned. Please, invest Newport at once.”

Clinton returned to his chair.

“Lord Charles,” Howe said to Cornwallis. “Pursue Washington, but only as far as New Brunswick.”

“And the reason for that?” Clinton heckled from his corner.

“To secure the New Jersey farmlands,” Howe continued with Cornwallis. “That way the army will cease to have supply problems. I will establish fortified posts in the wake of your advance.”

“They’ll be targets for attacks,” Clinton said.

“We needn’t worry about an offensive. We can take liberties with these people.”

“The military dictionary contains no such word as ‘liberties’,” replied Clinton. “If you choose not to crush Washington once and for all, then withdraw the army to Staten Island until spring; at least they’ll be safe from ambush.”

Howe smiled. “To quote our dear Murray: ‘the American native is an effeminate thing unfit for and impatient of war’.”

“I concur with Sir Henry,” Lord Percy interjected. “Such garrisons would make easy targets for an enemy in need of quick victories. Pull back to Staten Island and finish Washington off in the spring.”

“Lord Percy,” Howe said, “you’ve been involved in this conflict from the beginning. I think it has burdened you too much. You are in need of rejuvenation. You and Sir Henry should find Newport most restful. In fact, we could all benefit from rest.” He stepped away from the table. “Sir Henry, embark tomorrow. Lord Charles, begin operations immediately.”

Percy waited for Clinton as the room emptied. They stepped out of headquarters, their capes hardly needed in the unseasonably mild weather.

“He’s done us the nasty,” Clinton sighed as he put on his gloves.

“I’d laugh if it wasn’t so true,” Percy said. “Maybe he’s right – I’ve been at it too long.

I’m sick of it. I want to go home. I don’t care anymore.”

“Neither do I. As far as I’m concern, taking Newport is the last I will do. I’ll not baby-sit Lord Howe’s anchorage. I’m going back to England to clear my name for Charleston and seek a new command. I’ll petition Lord Germaine for the Canadian Army. Let Carlton or Burgoyne be Howe’s subordinates . . . You know, it’ll be a sad satisfaction when Billy slips . . . I wish Chatham was back. Let the North Ministry fall, the weaklings. If only the King could be forced to bring Chatham back; he’d reconcile with the Americans and then together we’d take on the French and steal the West Indies – there’s the cash.”